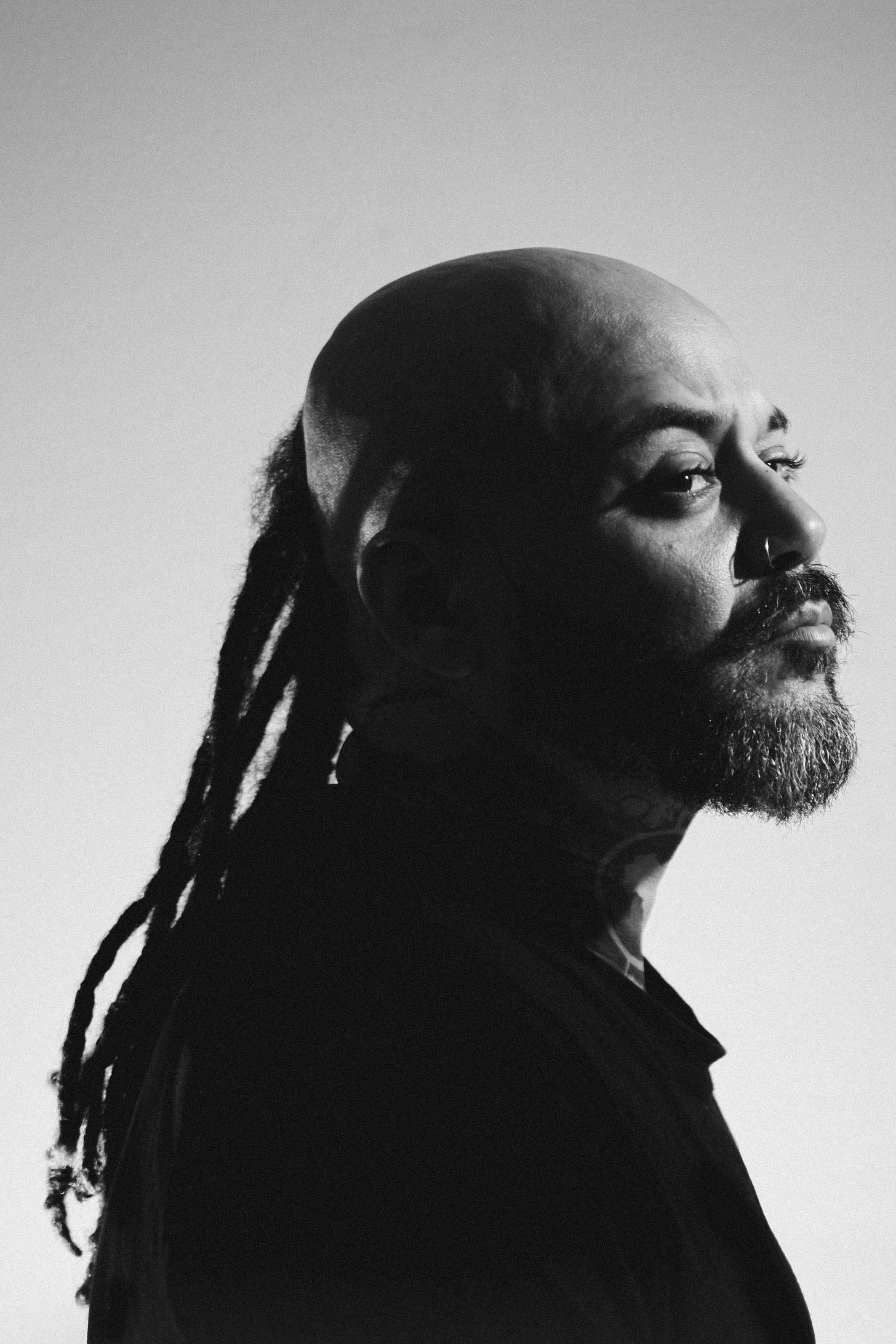

See that subtitle up there? It’s great when an artist is both self-aware and eloquent enough about his own art to basically do your job for you as a writer. Marcus Veiga, then man behind Scúru Fitchádu, is indeed all those things and more. He has been using a slogan recently that goes “from griots to riots”, and just in case you need clarification, a “griot” is “a West African historian, storyteller, praise singer, poet, and/or musician, (…) an ethnic group, which have the main responsibility for keeping stories of the individual tribes and families alive in the oral tradition, with the narrative accompanied by a musical instrument.” Which is precisely what Marcus is doing with his project regarding the culture of his Cape Verdean roots, with the same care and artistic sensitivity, but also with a pull-no-punches, all up in your face confrontational attitude that is sorely missing from so much supposedly rebellious music these days. And not just sonic-wise - lyrically, Marcus expresses himself in Cape Verdean creole (translations to both Portuguese and English are available, don’t worry), and his words are equally aimed straight at the heart of everything he is rioting against. This is poetry, with all the inherent beauty and impact of a real poet like he is, but as a warrior poet, his words go beyond “mere” beauty or aesthetical pleasing. Colonialism, privilege, their reflexes and consequences in a modern urban environment, so many of the things that corrode the utopian social harmony we often like to pretend exists, like ostriches in sand. Or, as the press releases puts it much better, “inspired by the revolutionary pro-African independence movements, their interventions, guidelines, and cultural legacies, establishing a conducting line to a poetic interpretation of the current urban spectrum.” Samples, traditional instrumentation, occasional guests, the rumble of the beastly bass beats, everything is a weapon to get the message across, to shake the cultural status quo. At the end of ‘Moku na el’, a sample in creole states something like “I work with a weapon in my hand. To violence, we respond with violence as well.”

Of course, we are here with the wonderful excuse of a new album being out, the fantastic ‘Nez Txada skúru dentu skina na braku fundu’ (meaning ‘in this dark upland at the corner in a deep hole’), which came out just like that, with little previous warning, a week ago. I’ve been fortunate enough to follow the project since the very beginning, and it has been incredible to watch its evolution. The original idea of mixing funaná, the music and dance from Cape Verde, with industrial/electronic beats and a vicious punk attitude, was already a potentially winning combination, but just as someone like Manuel Gagneux and his Zeal & Ardor playground, Marcus has been able to take a good idea and run with it - both musically and conceptually too - without resting too much on the initial laurels of having come up with it, and the strides have been enormous.

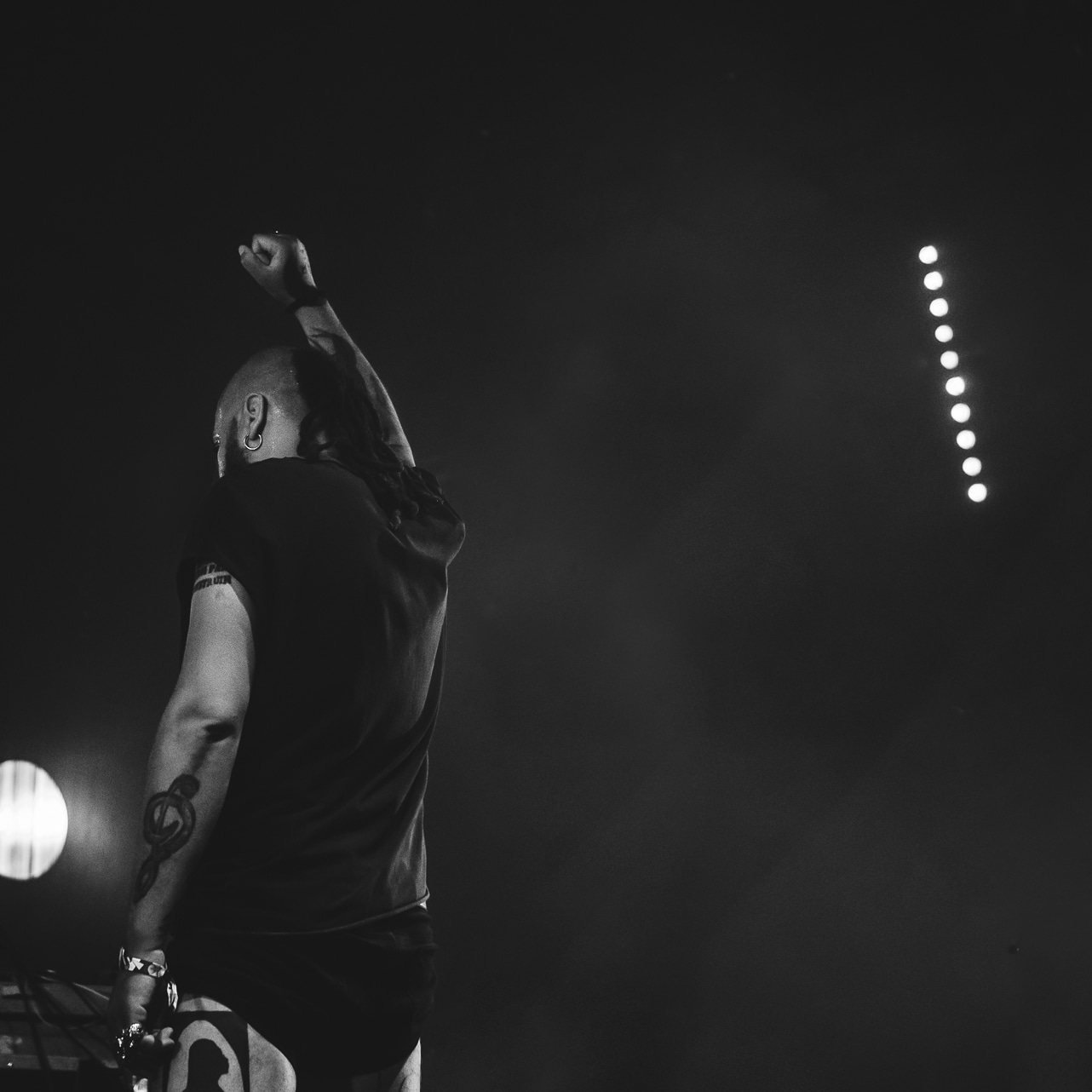

Although as a live band, Scúru Fitchádu were a massive hit from the start - seriously, it’s physically impossible to not start moving and throwing your body about with reckless abandon within the first few seconds of their already legendary, explosive shows -, the evolution in just a short few years in terms of the depth of songwriting has been remarkable. I remember mentioning them on a discussion group of a famous festival and sharing a song from the debut self-titled EP (2016), and everyone in the group was barely able to contain their vocal incomprehension. That’s what happens when you defy expectations. Now with this second album already in the bag, and after many excursions into international events where the intensity of the band and their purpose was felt like no other, few will be able to deny the impact of this music on every level. Remember the word “poetry” - yes, this is guerrilla music, yes, it’s meant to be uncomfortable and aggressive and confrontational and not in an escapist, or even allegorical way like so much “heavy” music is out there (which is fine, don’t get me wrong, we also need a lot of that), but there is also real beauty in here. Songs like ‘Strada Noti’ or ‘Korre Manuel’, while maintaining the lyrical intensity and bite, will instantly transport you to a Cape Verdean beach just as the sun goes down, a sad and pensive oasis-lullaby amidst the chaos of the rest of the world. Vocally, Marcus is looser than ever before too. Take the surprising Portuguese-sung cover of Mão Morta’s ‘Maria’, for instance, where the parallels previously established between his diction and that of the legendary Adolfo Luxúria Canibal are fully confirmed. There might have been the temptation before, by critics especially, to try to box the band in some kind of gimmicky category, some novelty way of presenting heavy music, but on this new album Marcus proves he’s beyond all of that, including that often misleading “heaviness” concept.

And that, to be honest, is already way too much talking about music that is absolutely immediate, despite its long-lasting depth and meaning. Go hear and buy the damn thing right now. Or just wait a little bit, because we have been fortunate to have caught Marcus for a little exclusive interview. Thank you Marcus, and thank you Scúru Fitchádu!

I like the unexpected and being predictable gives me hives.

—Marcus Veiga

[interview originally conducted in Portuguese]

This new record was announced all of a sudden, wasn’t it? Like, here’s a new one next week, deal with it! Is this a part of your musical guerrilla stance?

Marcus: Yes, absolutely, even though I had been threatening it for a few months with some little online thing or other which would indicate that I was preparing something soon, but still, my stance has always been like this. Sometimes a little impulsive perhaps, but I like the unexpected and being predictable gives me hives. I like this idea, the strategy of not having a normative strategy for releasing records. What matters is that I build an object that is on record timelessly, I’m very far from just going with the main streams. Mentally, I define when is the right time to put something out or not… usually it’s always in January.

Can you present us the album a little bit? What has changed for you since ‘Un Kuza Runhu’? To me it seems like a more collaborative album - have your companions and guests on the record changed the outcome of it substantially?

Marcus: This project is a bit more mature, since ‘Un Kuza Runhu’ is already three years old, if you think about it. There’s less fear of exploring other sounds, sounds that have been a part of my growth as an individual. Things that have influenced me and that I have been exposed to since I was young. I gave more time to exploring writing and orality. Though I’m still very proud of the previous record and of what it means to me… The pace of that record sort of became the calling card for Scúru Fitchádu. Knives out and everything a thousand miles an hour without worrying about details. That’s how some opinions full of clichés were created, which became repetitive and predictable after a while, and they managed to obfuscate any other incursion I could make outside of that universe. I still make music from the guts of heavy ambiance, but there’s more than that. This new album brings exactly what was hidden by the muscled scene, and in the process of mentally building it, I imagined a few guest participations, some happened and some didn’t. I think each of my guest fit perfectly with the main idea of their respective tracks. Though my creative and writing process is very lonely, Cachupa Psicadélica, O GAJO and Henrique Silva understood the direction and the concept and they interpreted them within their own universes.

Have your many shows, always so intense, influenced the way you write music? Do~you think about how a song will sound on stage when you write it?

Marcus: Yes! As I’ve mentioned before, the performance and catharsis before a crowd elements are what drives me the most to do this thing, so 90% of the music I write has to have that quality, has to be able to be interpreted live without losing its value, it has, above all, to fit a line-up of songs. I have my very own formulas of writing with that in mind, for example, since my first day of performing, I use a lot of interludes, and I make direct references to things that aren’t mine, but that add to the performance of the music, be it some Jello Biafra verses, a Norberto Tavares thought, or even a performance by Adolfo Luxúria Canibal or Justin Broadrick. Often, the same idea or intent that I put in these live incursions are the same I take to the room where I write. Everything is connected, texts are written already thinking of the way they will be delivered, not to mention that the way I write is really blast off, with the music turned up very loud as to emulate the feeling of a live PA. All very incorrect and nasty things of course… a real nightmare for any studio engineer.

What is at the origin of that process, what can kickstart a new song in your head? A beat, a lyric, an idea, a riff?

Marcus: Soundwise, it can be any noise, sample or riff. I use the tools I’ve always used, which is any device that is able to record voice. Actually, the initial idea is always meant to smash everything up, particularly for this record - the concept is to rise, it’s revolution, it’s guerrilla, but also mental freedom and the casting aside of the extras that castrate human beings, which led me to go over poetry made by guerrilla soldiers in the field, in books, songs and testimonies. Everything was used to make that connection.

Aside from guest appearances, Scúru Fitchádu is still pretty much you, in terms of studio/recordings, or has the concept of a band become to take any kind of place?

Marcus: Scúru Fitchádu is still me, as a pseudonym, so I keep this project lonely and marginal in its creation. A band concept, for me, is something much bigger than the aesthetics of performing, so if the band isn’t on the same page regarding ideas or ideals, its days are numbered. At least at this age where we’re not kids anymore, enjoying rock’n’roll on the road where everything goes. Working like this, I can spice up my art autonomously, without having to consider a collective approval. I’m constantly changing my live line-up according to the ambiance that I project or idealise, which really opens up possibilities. I don’t like predictable things, above all, and at the end of the day everything has to be aligned with the concept. For this new record, there is a very concrete idea, and it will be taken to the stage so that everything flows.

Let’s talk about the concept, then. How have you changed in that aspect, do you think? On the first spins of the album, you sound more confrontational, full of rage, even more than before. You can feel it’s a combat record. What is most important in the message that you’re passing here?

Marcus: The last record started with the same principles, but in a more anarchic way, shooting in every direction. I wouldn’t change a thing on it, but there’s hints there of what could be expected of this second chapter. ‘Nez Txada skúru dentu skina na braku fundu’ appeals directly to combat poetry, non normative, and above all to the mental decolonisation of Africans in Portugal and their afrodescendants, but also to questions to issues of the general social picture that we’re all a part of, with an anti-populist message. The title of the record (‘‘in this dark upland at the corner in a deep hole’) comes from a place that can be either of despair or a trench and headquarters towards the social conjecture, it can be a cold and dark place, but at the same time very visible and ignored. The lyrics deal with that concept of the title, always in a poetic perspective, many times subliminally, where there is the interpretation of the urban place, there is conflict of ideas, the mental prison inherited from colonialism, privilege and individuality. In fact, these ideas have always been present since the beginning of the project, thought they were too hidden by the package and delivery of the music. I constantly challenge myself to make art in a timeless way, that cuts through different times, art that can be considered both protest and cultural patrimony, be it today or many years from now.

I don’t like being boxed as the guy with the causes, because I don’t identify as being that preachy, I’m above all someone who writes and makes music, I can’t ghettoise my music just for that political limitation.

—Marcus Veiga

You gather a lot of different “tribes” in your concerts, is that a clear objective in what you do?

Marcus: I think that, even if it wasn’t planned, that reunion of tribes comes from the obvious mix of influences from very different universes, which is where I come from. It’s not really an objective of mine to bring people together, in fact I think that, even if people don’t understand zilch of what I’m saying, they easily identify the message and what brings them together is the same mindset, pro-freedom and revolutionary in intent. But there we go, I don’t like being boxed as the guy with the causes, because I don’t identify as being that preachy, I’m above all someone who writes and makes music, I can’t ghettoise my music just for that political limitation. As vehicles of art, we have the duty of delivering content in a responsible way above all… there is a code of conduct that should not be devalued.

Still, do you feel the value of the service that you are providing to African music, and to Cape Verdean music in particular? So many people being exposed to influences and even other artists that they might not reach without you as a bridge?

Marcus: I do feel that value, even if it’s not a concern of mine, because I know that many people don’t consider what I do African music. That exposition is natural, but I’m still far from that general recognition. First of all, I’m very far from being a popular product, the sound and the rhetoric of what I do don’t allow that, but also my structure is minimal, very small, and limits the access to someone who isn’t in any way into alternative music that is outside the main bright lights. Obviously, in 2023 people are already more enlightened towards Scúru Fitchádu, as a result of the concerts especially. I play my role in the spectrum of music, I make muscled and angry music that is placed right there in the darkest corner of that spectrum. I think I’m a good example that music, culturally speaking, doesn’t have to be predictable and normative.

As a listener and super fan of what you do, I feel that you’re still kind of scraping the surface of the potential your art can have. Do you feel like that? If you look at the horizon ahead, can you see yourself doing this for a long time?

Marcus: I constantly think about that durability, about the “what if one day…”, but the truth is that I don’t see myself doing this for many more years (Iggy Pop anyone?), I have been working towards me, as Scúru Fitchádu, not being just a synonym for chaotic live shows and lots of energy, but also something artistic, with substance and attitude that also works and gains value from that content. And that content can be delivered in a lot of different ways, with a lot of aesthetic tools, visual or sound. From griot to riots and from riots to griots, of course.

Find Scúru Fitchádu on Bandcamp, Spotify, Facebook and Instagram.