Being a fan of The Dirty Three and obviously of Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds for a long, long time, I was naturally excited when I read the news a few months ago that Warren Ellis was releasing a book, even before realising what the book would be about. I’m sure you will understand, if you have that kind of profound relationship with the music you love (and if you’re reading this, I’m assuming you do), or even with any other kind of art - if someone whose art you admire does something in any other medium, your curiosity is piqued. A musician that writes a book, a writer that paints, a film director that makes an album, it’s always a sort of different perspective into a creative mind that you have learned to admire through another medium. My excitement turned into piercing curiosity when I actually read what the book is about. Or at least, what is at the core of its narrative, which is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a piece of gum chewed by Nina Simone during her final performance in England in 1999. After the end of the concert, Ellis jumped on stage and grabbed the gum, wrapped it in the towel Dr Simone had left behind, and kept it (famously stored in a yellow Tower Records plastic bag) for years as a very special memento. As trivial an object as it seems to be, through the transcendent, transformative power of music - or perhaps more accurately the love of music - it nevertheless acquired an enormous spiritual significance, not just to Ellis but to other people. As he talked about it, fascination with this symbolic possession grew, and the book, in general terms, is the story of how the gum ended up in the Royal Danish Library for an exhibition, went on tour, inspired jewelry replicas and sculptures, all while sparking the creativity of people of all kinds of artistic realms, from curators to fashion designers to sculptors to other musicians.

That alone would be reason enough to recommend it thoroughly, as the story is bizarrely touching, but right from the first pages it becomes clear that ‘Nina Simone’s Gum’ is about much more than, well, Nina Simone’s gum. Ellis mentions at one point that he hasn’t written anything beyond emails since 1985, when he was studying and “handing in essays about books I had hardly read,” and while you could argue that it shows, it has to be a supremely positive argument - his language is straight and simple, always heartfelt and genuinely honest despite how to-the-point it always feels, and the 200+ pages of the paperback edition are an engaging, compulsive read despite the scattered - in the best possible sense, mind you - nature of the story. Memories, old conversations (often in the form of correspondence transcripts or text message chat snapshots), musings, lots of pictures of places, objects and events crucial to the stories being told, sometimes you have to stop yourself for a bit just to think about everything. Even so, I devoured the book in two days, as I’m sure you will too, if you haven’t yet.

It’s a brevity that will be inversely proportional to the amount of time some of Warren’s passages will remain in my mind. Most of all, this is a book about connection and meaning - how we connect with art, how it connects us with each other, and how everything can acquire a profound meaning and become an important symbol because of those connections. I posted this passage as a story in my Instagram account as soon as I read it a couple of days ago, because I think it really sums up a lot of what is discussed:

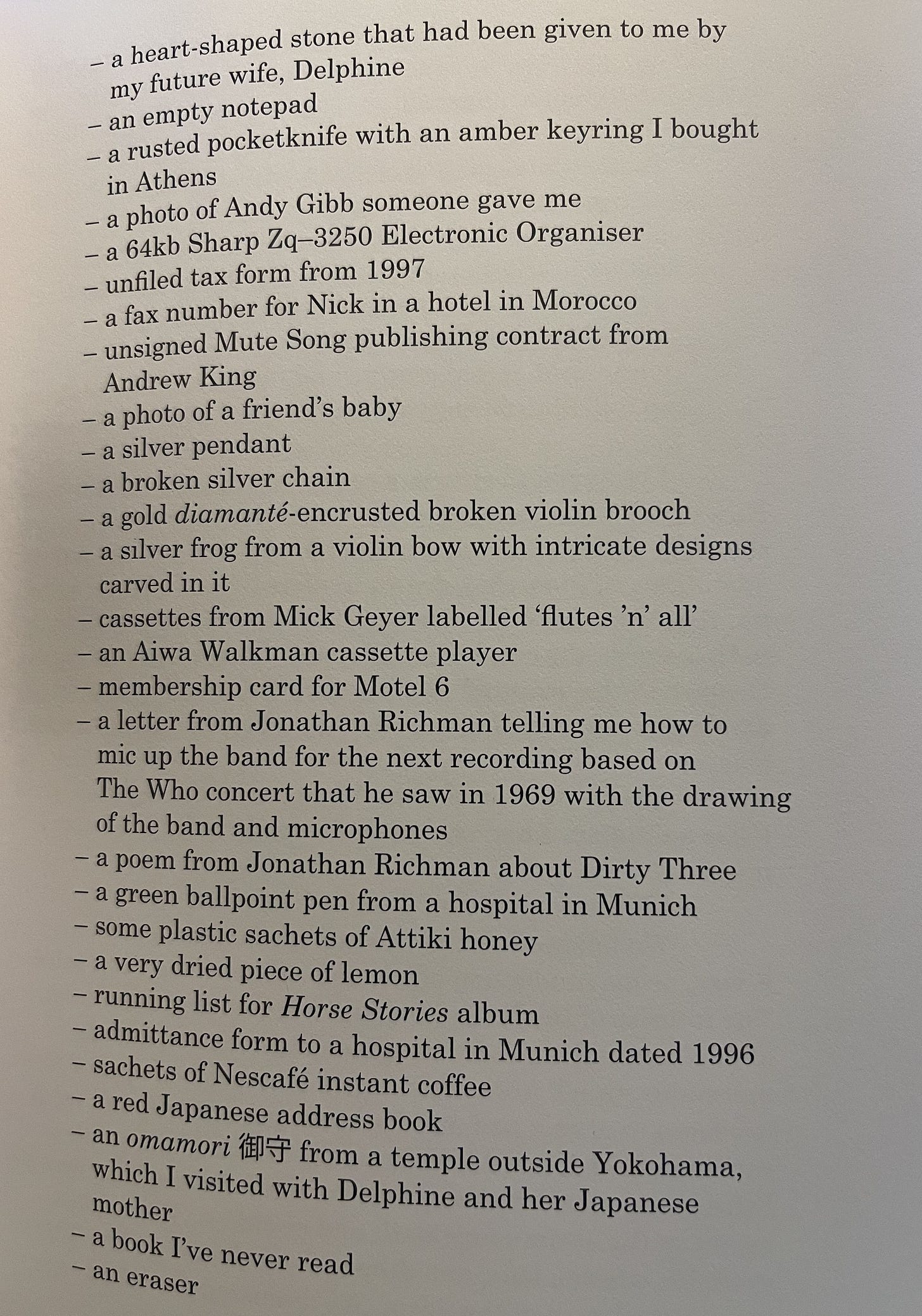

Though there is a strong biographical nature to the book, with some fantastic examples of how colourful a life Warren has lead so far (I am forever intrigued and fascinated by those clowns in the backyard - I mean, what the hell?!), a lot of it is instantly relatable to anyone who has any kind of passion by any kind of art. There’s a reason why guitarists throw guitar picks to the audience, why people scramble to rip the setlists from the stage floor after some shows, why people queue for hours in the hope that their favourite musician will sign a record. The ripples of the emotional effect your favourite records, paintings, books, sculptures or films have on you often spread to other connected items, and the magic they become imbued with is very real, at least to the person who feels that connection, a connection that is wonderfully explored with many great examples throughout this book, because Warren’s attachment to objects isn’t limited to the hallowed gum. Throughout these pages, there’s plenty of examples of mostly bizarre-sounding ephemera, and in fact some of my favourite passages are the lists of things he finds in some of his suitcases (mostly) that have accompanied his itinerant lifestyle along the years. Stuff like this:

Even if it’s not yours, you can totally imagine how each of those items is dripping with meaning, memory and importance. And no, not all of them are eternal, some of them are meant to be lost, given away or shared - like Nina Simone’s gum itself, in the end -, but that doesn’t detract from what they mean, to the initial carrier or to any of the subsequent ones.

I don’t have anything remotely as impacting as that magical piece of gum (does anyone?), but in my much more banal collection of mementos, there are equivalent things, tangible or intangible, as apparently worthless as they might seem to be. I wear a thumb ring at all times - admittedly, a bit of a douchey kind of accessory - because that was the first thing I bought at a festival that I attended as an accredited journalist. It might be scuffed and look like it belongs in the bin, but it feels like it’s a part of me and of what I do. Underneath my TV rests a drumstick that a famous metal drummer used to perform one of my favourite albums on stage on a very special show, I didn’t do anything special to acquire it, but when he threw it to the audience at the end of the show it literally landed in my arms. I look at it dozens of times a day, every day. And music obviously isn’t the sole generator of these sort of magical objects - after my grandpa passed away, the one possession of his that I wanted passed down to me, and that he wanted me to have, in an example of an object that has transcended its initial owner, is a Sporting Clube de Portugal shirt from the 1940s, given to him by the greatest goalscorer of all time (seriously, go see his goals per game stats), Fernando Peyroteo. I could write two whole books and still not properly transmit what that ratty 80 year old football shirt means to me.

Even the way I came about the book itself was a kind of “object story” in itself. Knowing the paperback edition was out, I went to the bookstore and looked for it in the usual places, and it wasn’t there. My girlfriend decided to ask about it (because I’m weird and that’s something I will only do in the most extreme of circumstances), and it turns out there was only one copy in stock and it was supposed to be on display. After a few minutes of searching, it turns out it was in the “music” section, separate from the rest of the “English literature”, and totally out of view because it had falled behind a row of other books. Like it had gone into hiding and had been waiting for me to go and get it.

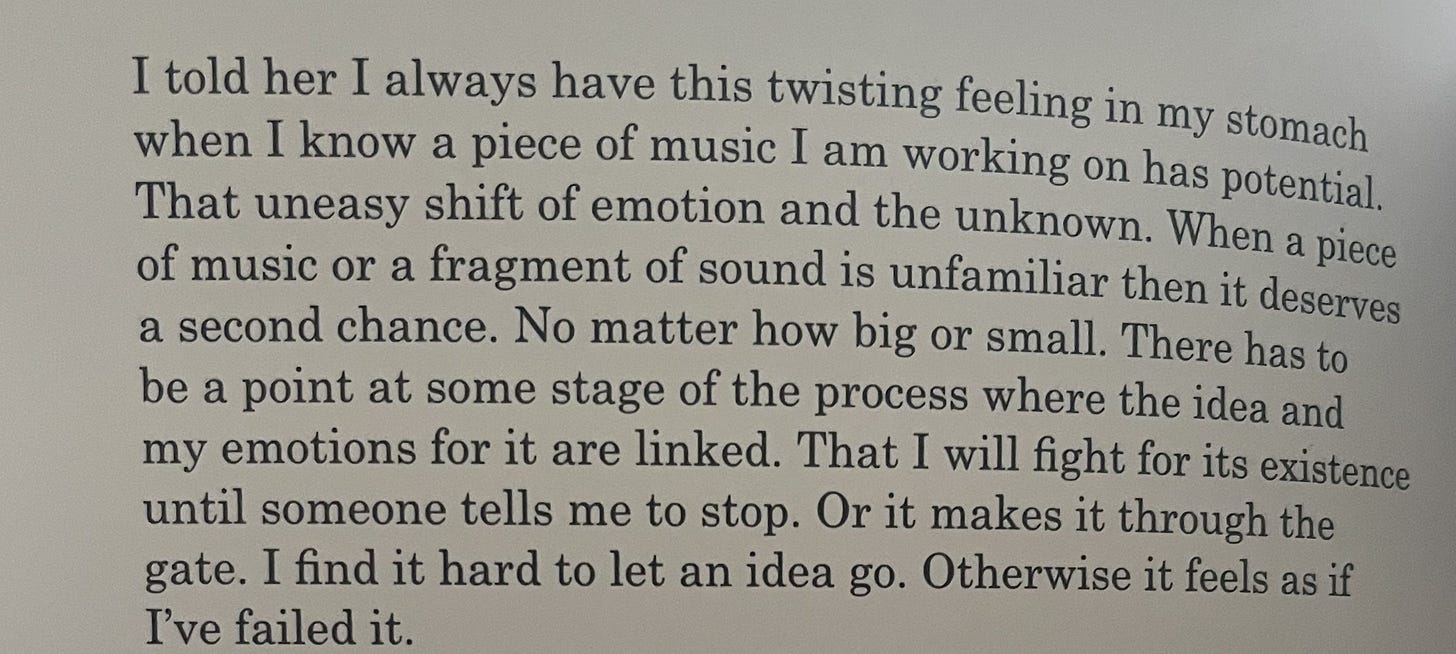

Another particularly interesting aspect of the book is the reflections it offers on several kinds of artistic creation. In a way, writing, either music or words, is also the process of imbuing something with meaning, and Warren makes that analogy himself when he compares the feeling he had when the gum was no longer in his possession with the “twisting feeling” of writing new music:

Even the writing of the book itself is subject of some reasoning, and while for a musician this might be a natural thing to mention in passing (he even compares how easy it is for him to write music as opposed to words), for me, as a writer, this hit home with a particular kind of potency:

I’ve been writing for just about 30 years, and I’ve often written about writing, but this puts that act of writing things down in a kind of perspective that I’ve never been able to verbalise before, and it will remain with me for a long time. Ultimately, that’s kind of the point of it all, isn’t it? What I’m feeling after reading this book, and how everything I’ve taken from it will in a way inform everything that I will do from now on, all of it is yet another ripple from that crazy act of a passionate fan jumping on stage after a show and stealing a piece of chewed gum over twenty years ago. And that in turn is a ripple from the effect of one of the greatest singers the world has known has had on everyone who has been touched by her voice and her songs and everything she was and meant, and still means. Music. Love. Connection. Creation. Bringing out the best in other people. Love.

No spoilers or anything, but the last words in the book (well, before the new afterword on this edition, but still) are “thank you”, and that’s really all I’d like to tell Warren Ellis after this amazing experience of reading his words and his thoughts. Thank you.